“One of my coworker’s sisters was texting while driving. She looked down and ran off the road and hit a tree. She flipped her car two times and was in serious condition at UVa medical center,” freshman Lucas Hobson said.

Almost all teens have a cell phone, and it’s hard to find a teen that does not text whenever they get the chance to. In the end, however, texting can have life changing consequences. According to a 2009 Virginia Tech Transportation Institute study, texting while driving creates a crash risk that is 23 times worse than driving while not distracted.

There are countless things that are distractions to drivers, and they can be as simple as constantly changing the radio station or communicating with passengers.

Texting, however, is one of the most frequent distractions, mainly because teens have become very addicted to their cell phones. Forty nine percent of teens admit that texting is the biggest distraction behind the wheel, according to the Allstate Foundation 2009 study “Shifting Teen Attitudes: The State of Teen Driving.”

“Texting and driving is a worldwide epidemic,” AHS driver education teacher Richard Wharam said. “Teens are addicted to the devices, and send 80 to 100 messages a day (2,500 messages a month)!”

The laws for this “epidemic,” however, have been going in and out of state legislatures for years.

Texting while driving is currently a secondary offense in the state of Virginia. This means that someone must be pulled over and charged for a primary offense to also be charged with texting (a $20 fine).

“I disagree with the current Virginia law listing texting as a secondary offense,” Wharam said. “It should be a primary offense with a heavy fine.”

However, with the current positive direction of House Bill 1907, future texting while driving laws could be drastically changed.

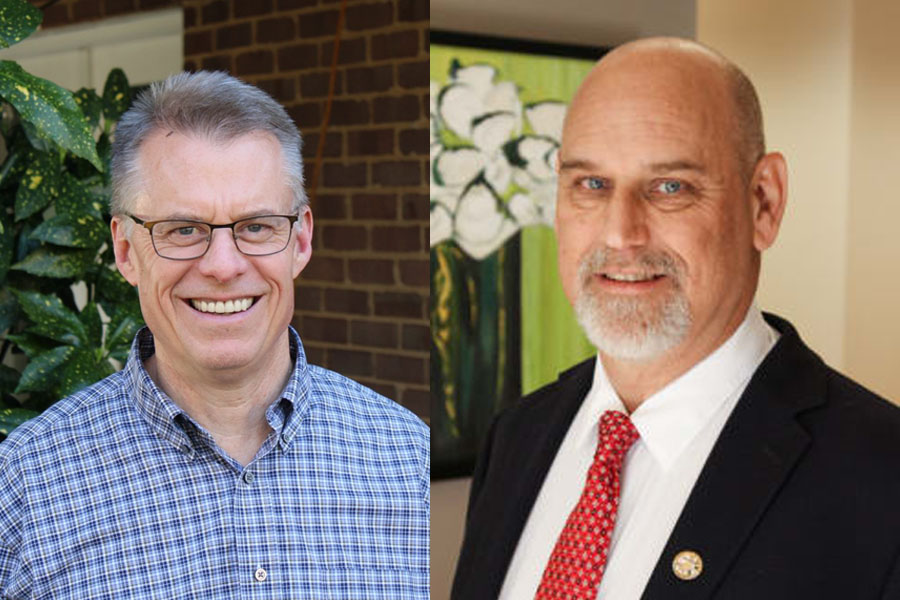

House Bill 1907, pre-filed in early January by Republican Delegate Rich Anderson, states that texting while driving will become a primary offense with a $250 fine for the first offense and $500 fine for a second offense. This means that any police officer can pull someone over and charge them if they are seen texting while driving.

On Feb. 5, the bill was passed through the Virginia House of Delegates with 92 “yes” votes, one of them from Republican delegate Rob Bell. Bell is the delegate representing the 58th district in Virginia, which includes Albemarle County.

“People are concerned,” Bell said about the issue. “It needs to be clear that you can get a fine for texting while driving.” Bell strongly feels that the bill will also successfully pass through the state Senate, which will then be signed into law by the governor.

Texting while driving might become a more disciplined violation, but is still a dangerous habit. Like most people, students at Albemarle recognize the dangers and consequences of texting while driving.

However, most students still choose to text and drive in a way they feel is somewhat safer, such as texting at a stoplight. This, among other texting tricks, such as driving with one hand or one’s knees, are not excuses for bad behavior. In doing this, the cell phone is still acting as a distraction to the driver even after the light turns green.

“I don’t think it’s OK for drivers to text at stop lights,” senior Danielle Horridge said. “It causes drivers around them to feel uneasy and can lead to fender-benders.”

According to the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, texting while driving takes a person’s eyes off the road for an average of five seconds. That same research shows that text messaging has the longest duration of “eyes-off-road-time.”

There are ways to avoid texting while driving, such as keeping a cell phone out of immediate reach while driving.

Other ways to avoid texting while driving can be found at the Allstate Foundation’s KeeptheDrive.com, an organization led by teens to educate their peers about safe driving.

Websites like this provide facts about the real consequences of texting while driving and promote safe driving habits.

“I really have no idea why students still text and drive when we are all aware of the horrible consequences,” Horridge said. “I suppose it goes with the teenage phenomena of feeling invincible and that ‘it will never happen to me.’ Our brains aren’t fully developed so it is harder for us to fully consider risks and easier for us to make hasty decisions and try to justify them.”

Either way, texting while driving is a serious part of distracted driving.

“Distracted driving is worse for teens because they are just learning to drive and are not experienced in recognizing dangerous conditions on the highway,” Wharam said. “Our pre-frontal cortex (front part of the brain) is not fully developed until age 25. The pre-frontal cortex deals with our denial. The older one gets, the better we are at controlling our denial.”

Students should not deny the fact that texting while driving can be a serious threat to themselves and other drivers. If House Bill 1907 becomes a law, even those who only text at stoplights are subject to a fine of $250. Legislature concludes a stronger law will definitely change the public’s opinion on texting while driving, since the overall dangers obviously have not.

“When children die because of a collision involving a distracted driver, it’s time to say ‘no,’” Wharam said.