For many high schoolers, the thought of college and the future is very stressful. Competing against fellow classmates, many students challenge themselves with Advanced Placement, or AP, classes.

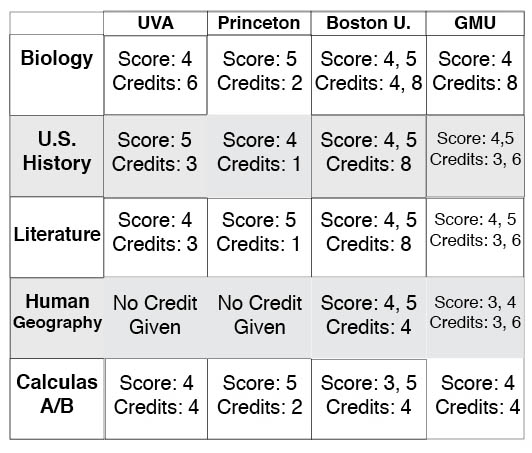

Beginning sophomore year, students are offered the choice to take this heavy set course in several different subjects, including history, English, science, or math. Not only are students asked to challenge themselves academically by take a “college level” class, but they can earn college credit with high scores on AP exams at the end of the year.

Even though the $89 fee for an AP test might seem high, with a single class at UVA costing about $1200, students could save substantial amounts of money by earning college credit through AP tests. Some students are even able to start their college career as sophomores instead of freshmen, having the opportunity to graduate early in return.

However, some colleges are starting to challenge the idea that students should be rewarded with college credit for taking a challenging high school course.

Dartmouth College, the elite ivy league school of Hanover, New Hampshire, recently sparked an outcry from many wishful high school students and their parents after they decided, starting in the fall of 2014, that they would no longer give credit to high scorers for any AP exams.

Dartmouth isn’t the only school to have decided this. Other schools such as MIT, the University of Pennsylvania, and St. John’s College already give little or no credit for AP tests.

One reason that schools are making the decisions not to accept AP credit is because they believe the courses are “watered down” and students are not fully prepared for more advanced coursework if they skip the introductory level courses. For example, a student might not be prepared to go directly to PSYCH 102 after skipping PSYCH 101 because of their score on the AP Psychology exam.

In fact, according to a Jan. 13 “Inside Higher Ed” article, Dartmouth conducted their own experiment with their psychology students. They found that 90 percent of students that earned a 5 on the AP Psychology test were unable to pass their placement test for an introduction to psychology class. Those students that went ahead and took the introductory class anyway did not perform any better than students who had not taken AP Psychology.

This is not to say that colleges don’t want students to take the AP courses, they just don’t want to also award them college credit for them. Students still need to push themselves and take advanced coursework in order to be accepted to competitive universities.

Such actions have many students worrying, especially since many are taking multiple AP classes, and have been for a several years now. Students are wondering what led schools to make this choice. It also causes commotion among students, whose plans to save money or graduate early now comes into question.

Junior Savannah Maxwell, who plans on taking four AP classes for her senior year, does not agree with some colleges and their changes to the AP credit policy. “It’s pointless not to accept credit for a class that students put so much effort into.”

Former student, Liana Bayne, AHS ’09, who graduated from Virginia Tech in December, said, “The backlash is probably coming from schools that don’t think their STEM (Science Technology Engineering Math) types are as prepared to skip intro classes, even with a 5 on the AP exam.”

Bayne, who took AP courses in English, as well as in history and Spanish, found many advantages going into college. She began her university career six credits shy of being a sophomore and was therefore able to graduate early. She was most proud for earning her AP Spanish credit, as it ultimately allowed her to double major in English and Spanish.

While some colleges believe that high school AP students may face difficulty taking a college-level class, Bayne believes otherwise. “I can tell you that tenth grade AP world history with Mrs. Dyer was way more rigorous than any college class,” she said.

Although this decision is getting mainly negative feedback, guidance counselor Michael Massey has a positive outlook on the situation. “Hopefully it will force students to take courses appropriate for them, rather than courses that will help get credit for them.”

Massey also does not believe that this will affect Albemarle and the way students go about making class choices. He said, “I think our programs are established enough that they will stick around regardless of what policies [are made].”